Fig 1: Fanny Palmer Austen’s Silhouette by John Meirs.

In the early nineteenth century, families treasured images of their loved ones, images created by way of drawings or portraits in oils. A popular, cheaper, alternative source of portraiture was the silhouette. Among known silhouettes of members of the Austen family[1] is one of Fanny Palmer Austen.[2] We don’t know at whose behest a sitting was arranged, but sometime after she arrived in England in 1811, Fanny’s silhouette[3] was taken in London at the fashionable shop of Meirs and Field at 111 The Strand. What does Fanny’s silhouette reveal about her appearance, even her character?

What is a Silhouette?

In the eighteenth century blackened cut-paper images became a highly favoured form of miniature portraiture. According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, this fashion for profiles arose in part from a resurgence of interest in neoclassical design that grew in the 1770s at the time of the archaeological discoveries of ancient Roman sites at Herculaneum and Pompeii. Apart from cultural and historical interests, silhouettes came to be valued as reminders of one’s family and friends. Portrait artists set up business in large centres, including London. Images were quickly executed, readily copied in multiples and offered at very affordable prices, ranging from about two shillings to one guinea. From 1788 to 1821, John Meirs was highly acclaimed for his skills in this art form. He is said to have amassed 100,000 profiles in his shop by 1821. At his death, his estate was worth £20,000 pounds.

Making Fanny’s Profile

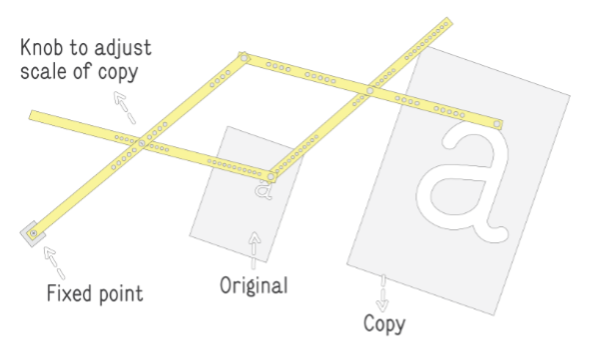

The procedure was straightforward and efficient. Fanny would have been positioned on a chair, in front of a glass screen behind which was affixed a sheet of plain paper. By remaining absolutely still for a few minutes, light from a candle beside her would cast her shadow on the sheet of paper, allowing John Meirs to rapidly trace her life-size profile on it. He then used a pantograph to reduce the size to 6½ cm. by 8 cm.

Fig 2: “Method of Taking Profiles,” Ladies Monthly Magazine, October 1799.

Fig. 3: How a Pantograph Works.[4]

Fanny's silhouette shows her head and shoulders.[5] Here is a young woman with a short neck, rounded features and a fashionable hairstyle. Her long locks are twisted and caught up at the back of her head, with the suggestion of curls on her forehead.

The image still required finishing touches. First, the profile was painted black and affixed on an oval of plaster. Then, Meir’s young partner, John Field, would have enhanced aspects of her head, her hair and shoulders by a process known as “bronzing.” To this end, he used gold paint to highlight contrasts of texture and detail. The finished product was put under glass, secured in an oval frame and mounted on a rectangular black background board.[6]

Revealing Character - Conveying Likeness?

The popular views of Swiss poet and theologian Johann Kaspar Lavater, author of Essays on Physiognomy,[7] fueled nineteenth-century speculations about what a silhouette revealed. According to Lavater, who illustrated his book with many black profiles, it was possible to discover a person’s character by concentrating on an individual’s main features. Such examinations would reveal both virtues and vices. Profilists, such as Meirs, were also attracted to the idea that one’s appearance was revelatory of character. His trade label, affixed to the back of Fanny’s profile, claims that he “executed likenesses in profiles with unequalled accuracy which convey the most forcible expressions of character.”[8] Meirs most likely hoped that such a claim would advance his business, in light of its consistency with Lavater’s popular views, but he wisely refrained from inferring specific, “expressions of character” from his profiles, leaving that conjectural task to his clients and their friends.

Twentieth-century silhouette collector Peggy Hickman, in an article titled “Silhouettes from Jane Austen’s Family”[9] treats Fanny’s silhouette as a source of information. She alludes to Fanny’s physical features. According to Hickman, Fanny was “no beauty,” rather a young woman with “blunt features and a short, thick neck.”[10] This seems unfair. True, Fanny’s neck is short but she was of petite stature, so the size of her neck can be viewed as proportionate to the rest of her body. In addition, blunt features, as they appear one-dimensionally in profile, may not form so unattractive a face when viewed from a frontal perspective. Hickman’s assessment of Fanny’s lack of beauty seems unnecessarily harsh on slight evidence.

Hickman also appears sympathetic to Meirs’s sentiments about what a profile can convey. In particular, she ascribes a “determined expression” to Fanny. She does not explain what she considers to be indicators of determination- might they be the shape and positioning of the mouth? However, simply observing the area around Fanny’s mouth could just as easily trigger other assessments of what her expression conveys. Moreover, without a fuller description and accompanying qualifiers, it is unclear whether Fanny’s so-called “determined expression” is meant to indicate a desirable character trait or not. In some situations, it could be good to be resolute, in others, being adamant or single-minded would indicate a deficit of character. Hickman adduces no other sources of information about Fanny’s attitudes, behaviour and opinions which would independently confirm Fanny was a “determined” individual. Even if she does look determined, perhaps this was just a fleeting expression which Meirs happened to catch and not an indicator of an established character trait.

Conclusion:

Fanny’s profile has definite merit from an aesthetic point of view. It is a beautifully executed example of Meirs and Field’s mastery of their art. From an informational point of view, the silhouette does convey some limited details about Fanny’s physical features, in particular her interest in the style of the day, as witnessed by the fashionable arrangement of her hair. Yet, taken as a putative indicator of her character, Fanny’s profile is a disappointment.

Other materials are needed for a fuller appreciation of Fanny in all her complexity. Significantly, there is one other visual representation of Fanny, a portrait painted in oils in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1810 by the talented British artist, Robert Field.

Fig. 4: Robert Field’s portrait of Fanny

In it, he captures his subject’s face in full, frontal detail, including her wonderful red-gold hair, her pleasing figure, serious and candid expression, clear blue eyes and direct gaze. By dint of its artistry, this representation of Fanny is a richer, more evocative image than the inherently limited, one-dimensional silhouette. A full appreciation of an individual’s character depends in addition on her opinions, thoughts and actions. Notably, Fanny’s surviving letters, written in 1810 and then continuing from 1812 to 1814, give evidence of a brave, loyal, caring and affectionate woman, wife and mother.[11] A study of these documents yields a treasure trove of information about Fanny’s character that is far more revealing than whatever clues may be adduced from her profile.

All things considered, Fanny’s silhouette deserves appreciation as the intricate and handsome object that it is, as well as the associations it may trigger for further consideration.[12]

[1] There are existing silhouettes of Rev and Mrs. George Austen, Cassandra Austen, Edward Austen and his adopted parents Thomas and Catherine Knight and also one said to be of Jane Austen.

[2] Fanny’s profile on plaster was retained by her husband, Charles Austen, and his succeeding family for 110 years after her death until his grandchildren, spinster sisters Emma Florence and Jane, sold it to Mr. Frederick Lovering in 1924. When his collection was auctioned in 1948, the silhouette was bought by Peggy Hickman.

[3] What we would today call a silhouette was then known in England as a “shade” or “profile,” if it was a portrait.

[4] Deirdre Le Faye outlines this procedure in her article “Silhouettes of the Revd William Knight and his family,” The Jane Austen Society Report V, 138-39.

[5] Thanks to Darren Bevin of the Chawton House Library for providing the dimensions of Fanny’s profile.

[6] This copy of Fanny’s silhouette can be seen in the Oak Room at Chawton House, Chawton, Kent.

[7] It was published in translation from the original German in 1793 and became a best seller in England. See Le Faye, “Silhouettes of the Revd William Knight and his family,” 137.

[8] Alternative wording on a Meirs profile of 1813 speaks of it conveying “the most forcible expression and animated character”

[9] Peggy Hickman, “Silhouettes of Jane Austen’s Family” in Shades from Jane Austen, written and illustrated by Honoria D. Marsh and Peggy Hickman, Perry Jackson Ltd, 1975. Hickman was an early owner of Fanny’s silhouette, acquiring it in 1948. After her death, it was sold in 1993 at auction for £2,020. Later it was acquired by Sandra Lerner, who gave it to the Chawton House.

[10] Peggy Hickman, “Silhouettes of the Austen Family,” plate XV.

[11] Fanny’s letters are held by the Morgan Library and Museum, New York City, MA 4500. They are contextualized and explored in my book, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister: The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen, MQUP, 2017. 2018.

[12] A version of this essay appeared in The Jane Austen Society Report for 2016, 23-27.

![Fig 1: The Terrace Southend, 1808. Note the bathing machines waiting for clients on the shore.[4]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639368925-URADIU6JO9HEDA5V10GH/Terrace.jpg)

![Fig. 2: Sketch of the Royal Hotel[7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639463137-ORT0XKQ9UBTITZD8GNID/Royal+Hotel.jpg)

![Fig. 3: The purpose-built Library is the building on the far right.[13]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639531617-7LCL4HWN62JI5XBDZDYL/Terrace+Library.jpg)

![Fig 5: The Royal Terrace and Royal Hotel[20]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1629639673586-Q5A6HA2KV6GTL3XYO034/Royal+Terrace+and+Hotel.jpg)

![Fig. 1: The Commissioner’s House,[4] where one of the balls was held.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1627340553553-OIGEJFXWH8JUPJF1PHX2/Commisioner+House.jpg)

![Fig. 2: General William Dyott, formerly Lt. Dyott.[7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1627340681757-SV5NCBFQ09ZUO6CBXBUF/Dyott.jpg)

![Fig: 6: Admiral Herbert Sawyer, c. 1811, Charles Austen’s Commander–in-Chief on the North American Station and brother of Sophia.[18] ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1627340887979-JOO7F4TZKPDNYYD6TU2D/Herbert+Sawyer.jpg)