The 250th Anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth has prompted world wide recognition of her literary legacy, including a celebration in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Around four hundred people recently gathered beside the iconic Victorian bandstand in the Halifax Public Gardens to enjoy a sequence of readings from Austen’s six published novels, her poems and prayers. The summer sun shone, the wind blew, and by times a harpist played and sang music of the Regency period. It was a wonderful afternoon.[i]

The timing and place of this event was particularly appropriate. It occurred on Sunday, 17 August, 2025, 2011 years to the day when Jane was thinking about the art of writing. Having worked thorough a draft manuscript of her niece, Anna Austen, Jane wrote her a warm and supportive letter. She offered constructive suggestions about the development of her characters, the authenticity of her settings and her dialogue. (Letter to Anna Austen, No. 104, Jane Austen’s Letters, ed. LeFaye, 268-269.) Although Jane Austen would have no way of knowing about our Halifax event in 2025, I like to think she would be pleased that there continue to be special occasions for enjoying the delights of her fiction and her skills as a writer.

Halifax is one of the two places in North America, where Jane Austen’s naval brothers, Charles and Francis, lived and worked. Such a historic connection marks this city as a perfect location for celebrating Jane Austen at 250.

During the event, I spoke about the Austen family’s connections to Halifax. Here is the illustrated version of my talk. Following that, you can discover a photo gallery of images capturing the look and spirit of Jane Austen in the Public Gardens.

………………………………………………………………………….

Fig. 1: Captain Charles Austen by Robert Field

Jane Austen never came to Halifax, Nova Scotia, but two of her brothers, Charles and Francis, were here while serving on the North American station of the Royal Navy. Jane avidly followed their careers and drew on their naval experiences when she wrote Mansfield Park (1814) and Persuasion (1818), novels which contain significant naval characters. Charles’s time in Halifax coincided with Jane Austen’s writing life. However, Francis’s associations occurred decades after Jane’s death in 1817.

The young Captain Charles Austen arrived first. On 6 August 1805 he brought his newly built sloop of war the 18 gun Indian into Halifax harbour on her maiden voyage. During 1805-1811, he stayed in Halifax a number of times, initially with the Indian, then in 1810 with the Swiftsure (74 guns), and finally with the frigate, Cleopatra (32 guns). Otherwise he was on mission at sea, or working in and out of St George’s Bermuda, the southern base of the Station.

These were dangerous and tumultuous times as the Napoleonic wars with France and Spain challenged and stretched the resources of the British Navy. Charles and the squadron were required to cruise the North Atlantic to protect British trade while interrupting enemy commerce, and to escort convoys of British troops and merchantmen. A side benefit of this tedious work for Charles and his men was the chance to earn prize money.

Fig. 2: Andrew Belcher, Charles’s Prize agent, by Robert Field

Enemy ships and cargoes seized during wartime could be condemned as lawful prize in a local Vice Admiralty Court. Thereafter they would be sold by auction and the prize money would be distributed among all members of the capturing ship(s). Charles was delighted when the Halifax court approved his co-captures of a Spanish schooner, the Rosalie, a Swedish ship, the Dygden, and part of the cargo of an American ship, the Ocean. He kept in close contact with his prize agent, merchant Andrew Belcher, at his office on Lower Water Street. Unfortunately, incomplete court records do not report Charles’s income from these three successful adjudications, but he may have received as much as £250, about the equivalent of a year’s pay at his rank. At home in England, the Austens would be excited to hear Charles’s news about his prize money. Jane Austen later made good use of the prize money theme in her novel, Persuasion. She created a hero, Captain Frederick Wentworth, whose professional and social standing is enhanced by his accrued fortune from prize taking.

Continual cruising took a heavy toll on wooden sailing ships, which meant that Charles regularly brought his vessels into the Naval Yard (located at the Narrows on the west side of Halifax harbour) for repairs and refits. He stayed at hand to ensure that the sail makers, shipwrights, caulkers, joiners, chandlers and others rendered his ships seaworthy. Although the original Naval Yard has been totally rebuilt for the Canadian navy, you can view an intricate model of the Yard as it appeared in 1813, at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Lower Water Street.

Fig. 3: From foreground to background: The Sail Loft, the Capstan House, the Careening Wharf[ii]

Fig. 4: Detail of the Sheer legs and Careening Wharf

Fig 5: Fanny Palmer Austen by Robert Field

In May 1810, Charles had quite a different association with the Naval Yard. Sir John Warren, Commander-in-Chief of the Station, promoted Charles to post captain and made him captain of his flag ship, HMS Swiftsure. Warren immediately required Charles to transport him and Lady Warren from Bermuda to Halifax and allowed Charles’s young wife, Fanny Palmer Austen, and their tiny daughter, Cassy, to accompany them. Once there, Charles and family were invited to stay with the Warrens in the Admiral’s quarters, which were attached to the Naval Hospital within the Yard. As flag captain’s wife, Fanny became the companion of the vigorous and redoubtable Lady Warren, a role she fulfilled with diplomacy and charm. Charles, meanwhile, had the great pleasure of time on shore with his beloved family, a rare luxury in wartime.

Fig. 6: The Naval Hospital, west face

Fig. 7: Naval Hospital, east face. The Admiral’s Quarters were in the far left wing.

Intriguingly, Fanny wrote articulate and insightful letters to her sister, Esther, in Bermuda, in which she described their new location and life style. Some letters reveal her delight in accompanying Charles whilep they moved in elite social circles as part of the Warrens’ retinue; other letters articulate her anxiety and distress when he was unexpectedly required to transport troops from Halifax to a war zone off Lisbon, Portugal. In later years, Jane Austen drew sensitive portraits of naval wives in Persuasion - depictions of the likable, practical, Mrs Croft, and the caring and thoughtful, Anne Elliott. Arguably, what Jane knew about Fanny’s life as a naval wife, were catalytic to these portrayals.

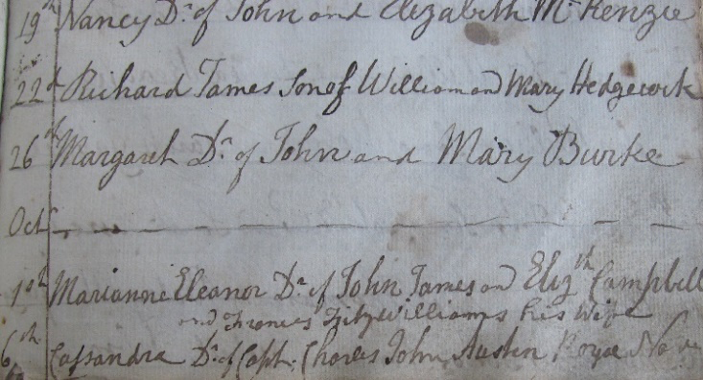

Two outstanding Georgian buildings in Halifax, St Paul’s Church (1750) and Government House (1805) were also part of the town which Charles and Fanny knew and frequented. On 6 October 1809, the rector of St Paul’s, Rev Dr Robert Stanser, the naval chaplain, baptized their daughter, Cassandra Esten Austen, at St Paul’s, an occasion which gave them a special family link to the church. In the summer of June 1810, they were the guests of Lt Gov George Prevost and Lady Prevost at a “splendid ball” (Fanny’s words) at Government House, where a delighted Fanny won $9 at the card game, Commerce.

Fig. 8: St Paul’s Church

Fig. 9: Baptismal entry for Cassy Austen

Fig. 10: Government House

Fig. 11: Admiral Sir Francis Austen

Sir Francis Austen in Halifax

Thirty four years after Charles left North America, Admiral Sir Francis Austen was posted to Halifax. He arrived on HMS Vindictive (50 guns) as Commander-in-Chief of the North American and West Indies Station, 1845-48. This was a time of peace and relative prosperity. His squadron was responsible for protecting the fisheries against American incursions, making coastal surveys, and maintaining a presence in waters adjacent to remaining British colonial territories in North America.

Sir Francis made his summer administrative headquarters at Admiralty House. He must have been pleased with the elegance and style of his official residence. Completed in 1819, this neo-classical Georgian building featured mahogany woodwork, marble fireplaces and decorated plaster ceilings, a far cry from Admiral Warren’s quarters at the Yard, well known to Charles and Fanny in 1810. A major part of Admiralty House still retains its original arrangement; it also houses a small naval museum. Today it is one of the buildings of CFB Stadacona.

Fig. 12: Admiralty House

Sir Francis proved to be practical and precise in his management of local naval affairs. He commanded a squadron of 13 ships, into which he integrated three then-new steam vessels. He was also concerned with the health of his men. Given the pleasing climate in Halifax from June through October, he set up a temporary hospital for patients employed during these months. By using the services of the Vindictive’s surgeon, the ship’s medical supplies and part of the old naval hospital, he was able to provide healthcare in better circumstances than the cramped conditions aboard ship.

While on shore in Halifax, Francis attended to his official duties but as far as social occasions went, he preferred the company of his immediate family, of which there were many: his sons Herbert (flag lieut) and George (chaplain), his nephew, Charles (flag lieut and son of brother, Charles), and his two unmarried daughters, Cassy and Frances, (social hostesses). Sir Francis was a caring father, concerned that his daughters could circulate comfortably in public. They, and the rest of his family, would surely have been welcome in the private, five-and-a-half-acre Halifax Horticultural Society Garden (laid out in 1837). It featured flower beds, winding paths, specimen trees, a pool and a stream. The garden occupied the southern half of the current Halifax Public Gardens, the part where we are now, including the original Horticultural Hall (1847), which is located behind you.

Fig. 13: Mature Elm tree dating to c. 1840s and Horticultural Hall

Jane Austen’s nephew, Charles (flag officer on the Vindictive) likely visited the Garden for his own romantic purposes. While in Halifax, he met and fell in love with Sophia Emma DeBlois, daughter of a local merchant, the late William DeBlois. The Garden was an ideal place for a courting couple to promenade, to enjoy conversations a deux, as well as summertime band concerts. Charles married Sophia on 6 September 1848.

If you are fascinated, as I am, by why and how members of the Austen family appear in the history of Halifax, an online walking tour, titled In the Footsteps of the Austens: A Walking Tour in Halifax, Nova Scotia, created by Sarah Emsley and myself is available on our web sites: sarahemsley.com and sheilajohnsonkindred.com.

………………………………………………………………………….

Endnotes:

[i] The event was organized by The Friends of the Public Gardens and The Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), Nova Scotia Region.

[ii] At the Careening wharf, a vessel was hauled out of the water, and turned on its side in order to clean, caulk and repair its bottom. Sheer legs, a two pronged lifting device, was used to extract or position a mast. Both were used for repairing and refitting the Indian in September 1809. See ADM 51/1991.

Further information on my website:

“Charles Austen and HMS Indian at the Halifax Naval Yard.” Post: 31 January 2020.

“Fanny Austen at the Halifax Naval Yard.” Post: 28 February 2020.

“Vice Admiral Francis Austen in Halifax Nova Scotia 1845-48.” Post: 27 November 2020.

Publications:

Sheila Johnson Kindred, “Two Naval Brothers, One City: Charles and Francis Austen in Halifax, Canada.” Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, ed. Sarah Emsley (2006), 9-21.

Sheila Johnson Kindred, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister: The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen (2017, 2018), Chapter 2:“On the Move: Between Bermuda and Halifax, 1809-1810 (33-50); Chapter 3: “In Halifax: Summer into Autumn, 1810” (51-72).

Photo Gallery: In the Halifax Public Gardens, 17 August 2025

Fig 14: Poster for Jane Austen in the Public Garden

Fig. 15: The setting: Halifax Public Gardens

Fig. 16: Darcy Johns, a reader, arriving at the Main Gate

Fig. 17: Sarah Emsley, MC

Fig 18: Jan Gidman, Regional Coordinator, JASNA NS reading from Mansfield Park

Fig. 19: Adria Jackson playing music of the Regency Period

Fig. 20: Dressed for the Occasion. Left to right: Linda Lefler, Donna Elliott, Anita Campbell, Joy McSwain, Sarah Emsley, Darcy Johns, and Adria Jackson seated

Fig: 21: From the Dahlia collection, “ Ketchup and Mustard ”

Fig. 22: Summer flowers in the Gardens

Fig. 23: Horticultural Hall (1847)

Fig. 24: Public Gardens Entrance, Spring Garden Road

Photo credits: Figs. 1, 5, 11, Private Collections; Fig. 2. AGNS; Fig. 9, St Paul’s Church; Figs. 8,10,12, Sarah Emsley; Fig. 18, Brian Gidman ; Figs: 16, 19, 20, 22, 23, Hugh Kindred, Figs: 3,4,6,7,13, 14,15, 17, 21, 24, Sheila Kindred.