Patrick Stokes, a great great nephew of Jane Austen and a direct descendant of her naval brother, Charles, died early on Christmas morning, 2023, at his home in Bridport, Dorset, England, aged 80. Trained as a chemist, Patrick had a successful international career in business. Among lovers of Jane Austen’s novels, he will be remembered for his initiatives to promote her literary legacy.

Fig.1: “Halifax,” by Lt Herbert Grey Austen, 1848. [2]

Fig 2: Publication from the Halifax Conference 2005. [3]

Patrick had a talent for gathering people together for literary purposes. He spearheaded and organized four highly successful international conferences attended by members of the Jane Austen Society UK (JAS), the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA) and the Jane Austen Society of Australia (JASA). These conferences took place in Bermuda (2000 and 2010) and in Halifax, Nova Scotia (2005 and 2017). The locations were apt choices as Jane Austen’s brothers, Francis and Charles, had both served in North American waters during their naval careers.[1]

Fig. 3: Plenary Speakers at the 2014 JASNA AGM.

In addition, for eighteen years Patrick organized and directed the highly popular annual JAS conferences in the UK, maintaining the tradition of choosing places associated with Jane Austen, her writings, her family and the period in which she wrote.

Patrick’s leadership in these matters was marked by professionalism, hard work, and humour. Those who had the good fortune to attend any of his conferences remarked favourably on the interesting speakers and the attractive settings with historic connections. They spoke warmly of the convivial spirit of the gathering, the fine food, and the pleasure of talking about Jane Austen in good company. The success of these ventures was in large part due to Patrick’s personality. He was charming, gregarious and made people feel welcome.

Patrick was also a memorable speaker about the Georgian Royal Navy.

Fig. 4: Patrick presenting at the Halifax Conference 2017.

He was a keynote speaker at the JASNA AGM in Montreal, 2014, and subsequently talked to JASNA Regions in the United States and Canada as well as in the UK. Patrick had a fine feel for the dramatic on such occasions, arriving with panache in the costume of an Admiral’s dress uniform of the period. His witty presentations amused and delighted his audiences.

Fig. 5: Patrick as an ‘Admiral’, Halifax, June 2017.

Patrick also displayed his acting skill when he was recruited to take part in Syrie James’s short play, “Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” which was performed at the 2014 JASNA AGM. He delivered a vigorous portrayal of the Prince Regent. In addition, participants in a JASNA summer tour to England will remember meeting Patrick on location at Lyme Regis. Who else could read so well the dramatic passages from Persuasion where Austen describes Lousia Musgrove’s disastrous fall on the Cobb at Lyme?

Fig. 6 : The novel Persuasion and Lyme.

Fig. 7: On location on the Cobb, Lyme.

Patrick rendered further service to JAS as Chair of the Society, beginning in 2004 for a five year term. Afterwards and ever willing to be helpful, Patrick took on the task of ensuring sufficient seating was available for JAS AGMs, which at the time took place in a tent on the grounds of Chawton House. With a twinkle in his eye and typical Patrick humour, he was happy to report that he was still a chairman, but now best described as a chair-man!

Fig. 8: Portrait of Captain Charles Austen in the 1840s.

Patrick was keen to promote Jane Austen to the world, to encourage new readers, to offer support to those researching her works, her life and family. It was in this context that I first met Patrick. While exploring the life and times of Fanny Palmer, Charles Austen’s young wife, Patrick’s knowledge, interest, and encouragement was a gift beyond expectation. I am very grateful for his permission to include in my book, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister: The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen,[4] reproductions of several Austen family artefacts in his possession, including a fine oil portrait of his great great grandfather, Charles, in later life.

I count myself very fortunate to have known Patrick. Along with wit and charm, he had a hugely generous heart and endearing spirit. His unique gift was to make everyone he met feel significant and important. Patrick will be greatly missed in the Jane Austen world and far beyond.

[1] Charles served as a commander (1804-1810), flag captain to his Commander- in - Chief, Admiral Warren (1810) and frigate captain (1810-1811); Admiral Sir Francis was Commander- in - Chief of the North American and West Indies Station, 1845-1848.

[2] Lt Herbert was a son of Admiral Sir Francis Austen and served on the North American Station with him from 1845-48. Private Collection.

[3] The cover image of Halifax Harbour is also by Lt Herbert Grey Austen. The publication was edited by Sarah Emsley and includes essays by Sarah, Peter Graham, Sheila Johnson Kindred and Brian Southam.

[4] MQUP ( 2017, 2018)

Photo credits: Figs. 2, 3, 6, 7 : Hugh Kindred; Thanks to Sarah Emsley for permission to use Fig. 4 and Fig.5.

![Fig. 1: The Kintbury Vicarage where Tom Fowle grew up prior to entering the Royal Navy.[1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1617022772451-39MJJGZTDS0NRJDYCU90/Kintbury.png)

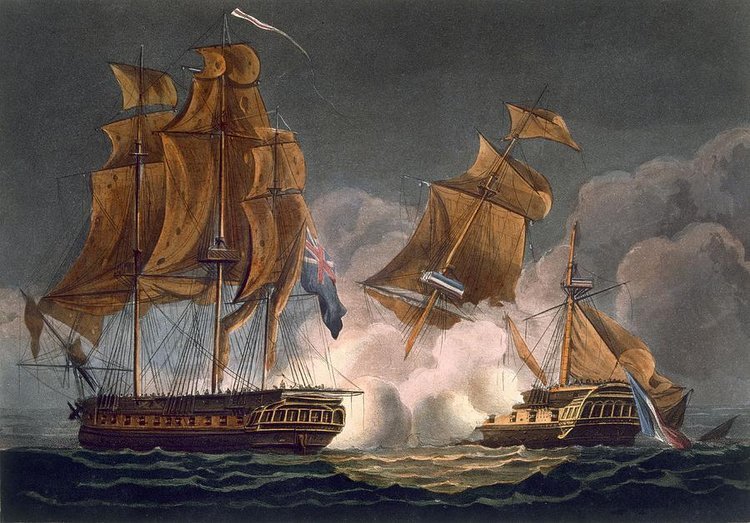

![Fig.2: HMS Atalante, of the identical design to HMS Indian (18 guns) on which Tom Fowle was a midshipman.[6]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1576625656873-H8MLTNYF3I89NE3BL89J/5.-HMS-Atalante-%28AGNS%29.jpg)

![Fig. 3: Captain Charles Austen, painted by Robert Field.[13]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1546809918031-H1EI95LLP45L9DUL5OE6/Charles+John+Austen.jpg)

![Fig. 4: Fanny Price with her brother William at the ball given in her honour.[24]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1617022984238-6FNP97YL419THR4X5MZZ/Fanny_Price.jpg)