Fanny Palmer Austen’s appearance in her fine portrait by Robert Field reveals much about her style. She is wearing a fashionable gown for this occasion, but given her transitory naval life, she must have found it challenging to maintain a modish style of dress. A review of her letters and pocket diary, and of her family interactions suggest how she managed her wardrobe according to fashionable Regency values and opinions.

Fig. 1: Fanny Palmer Austen by British portrait painter, Robert Field, c. 1810

Fanny Palmer Austen was about twenty-one when she posed for Field at his studio in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She is wearing a white muslin gown, decorated with what appears to be a muslin frill. Fanny is very much in the style of the day for woman of the gentry class favoured white clothing. Over her gown, she is wearing a pelisse, that is a long coat cut on the same lines as her gown. Fanny’s pelisse was constructed from wine-coloured silk and is lined in dark blue. Her headdress is made from “lustrous satin ribbon.”[1] Fanny’s overall sense of colour is good. Her white dress and the coordinated shade of her pelisse are choices which suit her fair complexion and light hair.[2]

According to Regency attitudes, “everything in a person’s ensemble revealed something about them to the Regency observer. Cut, fit and style were important for conveying the message.”[3] In Fanny’s case, we can see that her figure is slim and her clothes fit well; they appear to be sewn from fashionable fabrics, such as muslin, satin, and silk. In addition, Fanny’s hair style, which featured a cluster of curls about the face, was also very much in vogue. A portrait of Lady Croke (1808), also painted by Field, shows a similar way of arranging her hair. The image Fanny presents is reminiscent of Fanny Burney’s sentiment on what dress ought to do for its wearer - it should suit the style of her beauty and “assimilate with the character of her … gender and class.”[4]

The Field portrait provides unique access to Fanny’s clothing sense when she was in Halifax. When she sailed to England in 1811, her social spheres changed and, with them, the social influences on her. There were family visits to Jane, Cassandra, and Mrs Austen in the Hampshire village of Chawton, and to the wealthy and fashionable Knight family at Charles’s brother, Edward’s, country estate of Godmersham Park. Additionally, Fanny visited the London home of her parents at 22 Keppel Street. But during 1812 -1814 Fanny lived at sea where she made a home for her husband and young daughters aboard HMS Namur (74 guns).[5] Fanny needed to assemble and maintain clothing which suited her varied lifestyles. Her situation must have prompted a reassessment of her current wardrobe. Gowns that had been perfectly acceptable in colonial Bermuda and Halifax might not be so admired in more sophisticated British circles nor practical for living aboard ship.

Fig.2: Godmersham Park: Where Fanny visited with Charles in 1812 and 1813

For the Godmersham visits, which took place for two to one-week periods in July and October 1812 and 1813, Fanny would need clothes appropriate for the entertainments of the household. We can imagine her packing a variety of muslin gowns, including some suitable for formal dining and for visiting the Knights’ family friends in the neighbourhood. We know that Jane Austen carefully chose her clothes for one of her Godmersham visits. For example, a gown she “brought for special occasions, was insurance against any faux pas as to levels of dress, and would have [as current fashion dictated] been low necked.”[6]

Jane Austen provides a clue as to the effect that Fanny Austen created at Godmersham when both women were guests there in October 1813. According to Jane’s approving appraisal, Fanny appeared “as neat and white this morning as possible.”[7] To complete her look, she would need to have the appropriate outer wear: a pelisse of suitable texture and colour and perhaps several spencers.[8] Such garments, which could be worn indoors or outside, would provide style, and warmth on occasions when Fanny was driving about in the Knight carriage to view nearby Eastwell Park or exploring the gardens and paths on the estate. Sturdy leather walking shoes or half boots, with a leather lower half and fabric upper, were a must for country walking. Several pairs of elegant, decorative silk shoes would be useful for indoor gatherings and dancing. Some of these items would also be appropriate for Fanny’s lifestyle when visiting her parents in London. They lived in a fashionable part of the city, just off Russell Square, and they had a social circle of cousins and friends, that Fanny would join for supper parties when she was in town.

Fanny’s clothing needs were quite different while aboard the Namur. There were occasions when she needed to dress defensively to combat the extremes of weather. She had to be prepared for bone chilling fogs, blustery winds with driving rain and stormy seas as well as very hot days of unremitting sunshine. For winter wear, she required woolen dresses, pelisses, shawls, and mantles, and during the coldest months, Fanny most likely dressed in layers. Dress historian Hilary Davidson has speculated that Fanny’s purchase of a “waistcoat,” for 12s. 6d., as recorded in her pocket diary for early 1814, refers to a type of warm flannel undergarment, consisting of a “wraparound bodice, buttoning down the front, with gores for hips and bust.”[9] Red hooded cloaks made from red worsted wool were very popular for British outdoor country life. Such an item would protect Fanny during wet weather at sea and could be useful when travelling to join the Austen families in Kent and Hampshire and the Palmers in London.

Bermuda-born Fanny also knew the importance of being well protected on days of continuous sunshine. Not only did a straw hat provide respite from the heat but it offered a means for preserving an untanned, pale skin which was considered “the epitome of beauty.”[10] Fanny may have brought Bermuda-made straw hats with her to England, but if not, straw hats could be readily purchased in London. A directory for shops on Oxford Street, London (1817), listed ten straw bonnet manufactories.

By no means was all of Fanny’s wardrobe purchased. Like most genteel women of her time she had learned to sew and so she could satisfy some of her clothing needs while sustaining a modish style of dress. Her letters and pocket diary show that she was committed to constructing clothing and that she had the skills to do so. While in Halifax she made a tucker,[11] which she sent to Bermuda for her sister, Esther. She also created some “very tidy little spencers,”[12] including one for her nephew, Hamilton, and other items for her two-year-old daughter, Cassy. They were most likely short frocks and pantaloons as Cassy was proving to be a vigorous child. She does not write about making her own gowns, but it is at least likely that she could and sometimes did, although the fit might not equal the effect achieved by a professional dress maker.

While there were shops where drapers sold fabrics and milliners sold hats, ready made gowns were not always regularly for sale. Ladies who could not afford a bespoke gown from a dress maker or mantua maker, often proved to be ingenious in altering the basic shape of an existing gown to reflect more nearly the latest style. According to Hilary Davidson, “once their garments existed, Austen and her contemporaries sallied forth with confidence into amending, turning, and renewing them, refashioning clothes for as long as the fabric endured. …The point of alterations was not only to extend the life of a garment and prevent boredom with a limited wardrobe, but also to remain current, and to pass community scrutiny.”[13] Economies were never far from Fanny’s mind, given the uncertainties of Charles’s employ within the navy, so it is likely that the resourceful Fanny followed this lead and made the alterations which she thought would make her existing wardrobe fashionable once more.[14]

Another popular practice to enliven gowns was to add or replace decorative trims, such as ribbon, lace, flowers, fringing, and braid. As Davidson suggests, “haberdashery[15] applied in inventive, novel ways was a quick, cheap means of achieving freshness and fashion, a significant vehicle for a Regency women’s expression of individual taste when investment in a new garment was a large financial outlay.”[16] Fanny’s pocket diary for early 1814 records the purchase of ribbons, some of which she might have used for trimming a dress. Fanny had an example in Jane Austen who was a devotee of ribbon. She wrote Cassandra in March 1814 that she was “determined to trim [her] lilac sarsenet[17] with black satin ribbon just as my China Crepe is, 6d width at the bottom, 3d or 4d at the top.” In her opinion “ribbons are all the fashion at Bath.”[18]

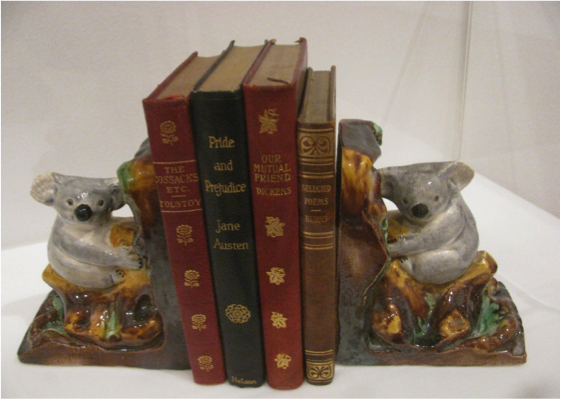

Fanny also practiced another widespread habit, that of creating one’s own accessories. In the back of her pocket diary for 1814 she recorded that 24 yards of thread[19] were required to make a purse, most likely by means of “netting.” Netted purses were highly popular. They also served a practical purpose for as dress styles had changed to a more flowing, classical look with the introduction of muslin fabrics, it was a convenient way for a lady to carry her necessities, such as a few coins and a scented handkerchief.[20] Fanny conceivably used the pattern she recorded to make her own purse. She may have also sewed reticules, which were another, popular type of small cloth handbag that was often richly embroidered.

Fig. 3: A reticule in the style of the 1790s. Satin stitch is used for the decorative strawberry motif.[21]

Fig. 4: A reticule in a design of about 1800. Note the tassels and beaded decoration.[22]

The female members of her Austen family had occasion to influence Fanny’s deliberations about fashion. During her visits to Chawton and Godmersham, Fanny would spend hours in the company of Jane, Cassandra and their niece, Fanny Knight, engaged in some sort of sewing. Perhaps they advised each other about how to best alter a gown so as to give it a more contemporary look. Or they may have exchanged views about the latest fashions illustrated in current periodicals, such as Lady’s Magazine, Lady’s Monthly Museum, or Ackermann’s Repository of Arts. [23] Jane Austen valued neatness and propriety in dress,[24] just the kind of opinions that informed Fanny’s perspective and were ultimately reflected in her own choices of clothes.

Fig. 5: Sewing was a significant and regular activity for genteel women.[25]

The Austen women likely also shared opinions about styles they individually observed on visits to London. Prior to the publication of Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1812), and Mansfield Park (1814), Jane spent time in London at her brother Henry’s house checking the proofs of each novel. Being temporarily in her brother’s social circle, she was well placed to notice current styles of dress. Fanny also spent time in London visiting her parents on Keppel Street, giving her opportunities to see the latest style in hats, the newest designs for sleeves, and the appropriate lengths for hems.

Fanny was fortunate that her naval connections gave her access to imported dress making materials, even during the trade restrictions of war time. While in Halifax, she received some unexpected yardage of India crepe, sent by Charles’s naval brother Francis, who was bringing home gifts for the Austen family from Canton, China. With this largesse, she had a Halifax dress maker, Miss Johnson, use part of the fabric to make up a gown for her sister, Esther. Fanny also had opportunities for shopping by proxy. While living on the Namur, she learned that another naval officer, Captain Baldwin, would happily take orders for “Handsome Velvets” from Holland “at about 4 Guineas the dress & also Sarsenets.”[26] She was willing to order some for her mother and her sister, Harriet, but not for herself as she did not think her family’s economy could support such an extravagance at this time.[27]

It is providential that we have the delightful portrait of Fanny when she was in North America, but a pity there are no paintings which show us Fanny’s appearance after she had arrived in England. Were such images to exist, I expect they would reveal a young woman who maintained the same good colour sense and simplicity of style, as are displayed in her portrait by Field. We may assume Fanny successfully continued to embody the changing look of the Regency period in her own personal way.

Fig. 6: Cover of Hilary Davidson’s book, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen Regency Fashion

[1] See Hilary Davidson, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen Regency Fashion (afterwards HD), Yale University Press, 2019, Fig. 7.2, 250. Thanks to dress and textile historian Hilary Davidson for the richness of information in this fine new book.

[2] In 1811 Fanny’s young niece, Caroline Austen described Fanny thus: “she was fair and pink, with very light hair, and I admired her greatly.” Reminiscences of Caroline Austen, ed. Deirdre Le Faye, 2011, 26.

[3] HD, 47.

[4] HD, 41.

[5] The Namur was a working naval vessel which rode at anchor at the Great Nore, the anchorage off Sheerness Kent.

[6] HD, 193.

[7] See Jane’s letter to Cassandra, 15 October 1813, in Jane Austen’s Letters, ed Deirdre Le Faye, 4th ed., 2011, 241.

[8] A spencer was a “short, close-fitting jacket, … [which] followed the form of the gown bodice over which it was worn” (HD, 286).

[9] HD, 70.

[10] See HD, 151. Nor was this only a feminine ideal: In Persuasion, Sir Walter Elliott makes a scathing comment about the appearance of a retired Admiral: “his face [was]the colour of mahogany, all lines and wrinkles, rough and rugged to the last degree … an example of what a sea faring-life can do.” See Persuasion, ed. R.C. Chapman, 3rd. ed. 1933, 20.

[11] A tucker was “a separate edging of linen, lawn, muslin or some other fine material, worn around the top of a low-necked bodice and tucked into it” (HD, 297). For Fanny’s mention of a tucker, see Sheila Johnson Kindred, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister (hereafter JATS), 2017, 66.

[12] Fanny Austen to Esther Esten, 14 August 1810. See JATS, 65.

[13] See HD, 121-22. There are many instances in Jane and Cassandra Austen’s correspondence which detail plans for altering and enhancing existing garments. As Davidson observes, “their correspondence demonstrates practical knowledge of dress construction: how many skirt breadths can be got from a length of muslin; where angled side gores need to be added” (HD,122).

[14] Fanny had another reason for altering her gowns, as she was pregnant twice between 1812 and 1814.

[15] Small items used in sewing.

[16] HD, 122.

[17] Sarsenet was a fine soft, silk material.

[18] Letters, Jane to Cassandra, 6 March 1814, 269.

[19] The thread would be either silk, cotton, linen or woollen.

[20] Small purses were a welcome change from the previous fashion of wearing “pockets,” bags with a slit opening tied around the waist under the skirt and used to carry one’s necessities. See HD, 83.

[21] Thanks to Joy McSwain of JASNA NS, the creator of this period reticule, for permission to photograph and reproduce the image.

[22] Thanks also to Darcy Johns of JASNA NS for permission to reproduce an image of the period reticule she has made.

[23] While at Godmersham in 1813 Fanny participated in another activity relating to fashion. She and her niece, Fanny Knight, took Fanny’s younger sisters, Louisa and Cass, to Canterbury to try on stays. Stays were a “close- fitting under garment, shaped and stiffened with whalebone, cording … and closed with lacing, which shaped the wearer’s torso” (HD, 296).

[24] See HD, 76.

[25] “Industrious Jenny Ever Useful Miss!! Employs Her Time In Making A Pelisse.” Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

[26] Fanny Austen to her sister Harriet Palmer, 5 February 1814. See JATS, 148.

[27] Even though Charles’s salary on the Namur was about £500 per annum, this was a temporary assignment and there was no certainty that Charles would be posted into another vessel when his term as flag officer for Sir Thomas Williams expired in October 1814.

![Fig. 3: A reticule in the style of the 1790s. Satin stitch is used for the decorative strawberry motif.[21]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1598396373948-U7NGTWT2WO9T4AF9HZR9/Reticule.jpg)

![Fig. 4: A reticule in a design of about 1800. Note the tassels and beaded decoration.[22]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1598396395632-8B6NP32TQOIADRTFVACN/Reticule_1800.jpg)

![Fig. 5: Sewing was a significant and regular activity for genteel women.[25]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c1547768ab722e48ecf1942/1598396430400-2QO7Q57VET7ICIEVAU92/Sewing.png)