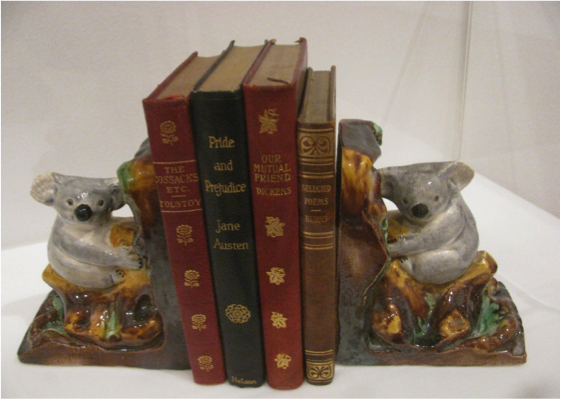

Captain John Shortland

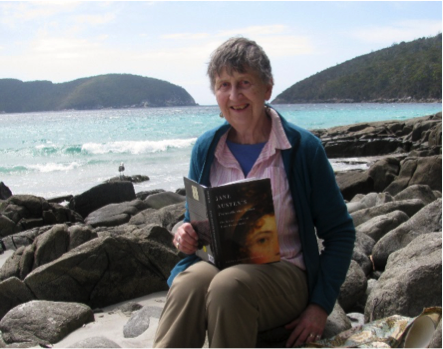

Charles Austen began his career as a ship’s captain in North American waters in 1805. In the six years that followed he served with a variety of other young men hoping to succeed in their naval careers. While I was researching my biography of Fanny Palmer Austen, Charles’s wife, I became curious about his fellow officers. What were their backgrounds? What had been their successes and failure? This quest led me to Captain John Shortland (1769-1810), who worked quite closely with Charles Austen on the North American Station of the Royal Navy during 1808-1809. While recently in Australia, I learned much more about Shortland’s earlier career there. These new details contribute to a profile of a courageous but ill-fated officer. Here is his story.

Hunter’s sketch of a wombat

John Shortland went out to New South Wales from England on the First Fleet,[1] initially on the Friendship as 2nd mate, but transferred to the Sirius, Captain John Hunter, where he was promoted to master’s mate just before the vessel arrived in Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788. Shortland found himself in a land very different from England. Human contact was limited to the company of other naval personnel, British administrators and increasing numbers of arriving convicts. An impression of the exotic fauna of the place is provided by Captain John Hunter’s contemporary sketch book, which included images of a wombat[2] and a platypus along with drawings of birds, flowers and fish encountered in the environs of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island.[3] Shortland was free to explore this remarkable new land between his naval assignments on board the Sirius.

In January 1789, the Sirius was despatched to the Cape of Good Hope, where the crew loaded foodstuffs and supplies at Table Bay and transported them back to New South Wales for the relief of the needy, fledgling colony at Port Jackson. In 1790, still aboard the Sirius, he sailed to Norfolk Island as part of an exploratory group sent to determine the Island’s suitability for settlement. Soon after the party landed, the unlucky Sirius was thrown upon a reef of rocks and sank. Shortland was thus stranded on Norfolk Island for the next eleven months.

He returned to England in 1791 but went back to Australia again in 1795 as first Lieutenant on the Reliance. He accepted the posting at the invitation of his friend, John Hunter, who had just been appointed Governor of New South Wales. According to the “Memoir of the Public Services of Captain John Shortland” in the Naval Chronicle, 1810, he undertook his transfer into the Reliance with “utmost reluctance and regrets and afterwards he considered his removal as the most unfortunate era of his life; as an event that banished him from the active scene which was opened by the [war with France].”[4] It seems that the challenges of exploration and colonization of Australia held less attraction than the chance to accrue prize money while the French war with Britain continued. Nevertheless, he stayed with the Reliance for the next five years, making voyages to the Cape of Good Hope and New Zealand as well as one journey which has earned him a place in Australian history.

In a letter to his father, Captain John Shortland Sr. he described an “expedition on the Governor’s whaleboat about as far as Port Stephens, which lies 100 miles northward of this place [Port Jackson]. In my passage down I discovered a very fine coal river, [on 10 September 1797] which I named after Governor Hunter. … Vessels from 80 to 250 tons may load here with great ease, I dare say [the river] will be a great acquisition to this settlement.”[5] Shortland enclosed an eye sketch of the estuary of the river and what is now known as Newcastle harbour, which he made in “the little time I was there.”

Shortland's map of Hunter's River from the Naval Chronicle of 1810

Shortland’s drafting and observational skills are evident from his sketch, which is done to scale. He made some soundings, identified the height of the tide, the location of shoal waters and rocks, and the channels navigated by his boat through the harbour. He indicated where fresh water could be found and described a long sandy beach, “bending towards Port Stephens about 14-16 miles.” Shortland indicated the presence of “natives” at two locations, including one close to where his party slept at the base of what is now known as Signal Hill, but it is thought he had no contact with them.[6]

Newcastle harbour entrance with Noddy's Island

Shortland’s lucky find of both the coal deposits and the Hunter River occurred, by chance, when he was sent in pursuit of some convicts who had seized the government boat, Cumberland, which ordinarily carried supplies between Hawkesbury and Sydney. Apparently, Shortland failed to apprehend the convicts. Nonetheless an enthusiastic Governor Hunter received Shortland’s subsequent report and immediately informed officials in England of his discovery of both the river and “a considerable quantity of coal”[7] at the base of Signal Hill on the south shore near the water.

Returning to England in 1800, John Shortland received various commands, before being made post captain on 6 August 1805. He was subsequently appointed to the Squirrel (24 guns). By 1808 we find him on the North American Station, where Admiral Sir John Warren posted him into the 40 gun Junon, a vessel recently captured from the French in February 1809. As Shortland was keen to have her ready for action as soon as possible, he is said to have put £1000-1500 of his own money into the Junon’s refurbishment at the Naval Yard in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[8] Amid the busyness of preparations, he found time to have his portrait painted by the accomplished British artist, Robert Field,[9] who happened to be working in Halifax, Nova Scotia. By mid September 1809, Shortland sailed from Halifax on a cruise, undermanned by about 100 sailors, but ready all the same for what prize captures he might make.

John Shortland was fortunate to get his first frigate, the Junon, but his luck did not hold. He had heard of a 20 gun French vessel, bound for Guadeloupe, and while in search of her in December 1809, the Junon was trapped by four French frigates off Antigua. They were the Renommée (40 gun), the Clorinde (40 guns), the Loire (20 guns) and the Seine (20 guns) and they showed no mercy. Shortland fought bravely until he was seriously wounded. After a gallant but hopeless action of 1¼ hours, the French broadsides smashed the Junon before her captors destroyed her by fire.[10] Captain Shortland was taken to Guadeloupe where he died of his wounds five weeks later.[11]

Shortland’s career in the Royal Navy had taken him world wide into new and uncharted southern waters. In his profession, he had been an ambitious and diligent naval officer, notable as an early explorer of coastal New South Wales, remembered as the first European to discover coal at Newcastle and to sketch her harbour. But sadly, while serving on the North American Station, he lost both his life and his ship.

Today a suburb of Newcastle bears his name. The motto of the local school is “Respect, Responsibility and Relationships.” This seems fitting for the commemoration of an individual of decisive action and faithful service to his country and his profession.

Shortland public school

[1] The First Fleet refers to the eleven ships that sailed from Portsmouth, England, 13 May 1787, in order to establish a penal colony, which became the first European settlement in Australia.

[2] Governor Hunter was given the gift of a live wombat captured on Preservation Island in the Bass Strait. When the wombat died, it was preserved in spirits and sent to Joseph Banks to be forwarded to the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. When a platypus was discovered in 1798, Hunter sent both a pelt and a sketch of it back to England.

[3] For information about Hunter’s sketches, see Linda Groom, The Steady Hand: Governor Hunter and His First Fleet Sketch Book, National Library of Australia, 2012.

[4] Naval Chronicle for 1810, July to December, vol. 24, 11.

[5] See John Shortland to his father, John Shortland Sr., 10 September 1797, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol.3, 481.

[6] The first published edition of the map in 1810 in the Naval Chronicle does not show the locations of native settlement. For a detailed reconstruction of his explorations, see “Lieutenant Shortland’s Survey of Newcastle on 9th September 1797” by H.W.W. Huntington, in hunterlivinghistories.com.

[7] See Governor Hunter to the Duke of Portland, 10 January 1798, transcribed from Historical Records of New South Wales, vol. 3, 727.

[8] Naval Chronicle, vol 24,.

[9] See the impressive miniature of Shortland, set in a gold locket. It is in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. The link is collections-rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/42038.html

[10] For an account of the battle, see the Naval Chronicle for 1810, July to December, vol. 24, 12-14.

[11] For the touching story of Shortland’s faithful dog, Pandore who was with him when he was dying in Guadeloupe, see Sheila Johnson Kindred, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister, MQUP, 2017, 64.