Zoom Presentation titled “Becoming Lt. William Price and Captain Wentworth: Charles Austen’s Naval Career in Relation to Mansfield Park and Persuasion to the Minnesota Region of JASNA, on 11 November 2023 at 12:00 - 1:30 AST.

Captain Charles Austen’s Ceremonial Spadroon

A naval captain’s awards and gifts in recognition of meritorious service are springboards to understanding the diversity of his professional career and his versatility as an officer. In the case of Captain Charles Austen, brother of Jane Austen, two special objects merit exploration.[1] I have already written about the significance of Charles’s General Service Medal with its two clasps, one, referred to as “Unicorn 8 June 1796,” was awarded for his participation in the impressive capture of an enemy vessel, La Tribune (44 guns), and the other for the campaign for “Syria[2] Charles received this distinguished British naval award in 1849. A very different mark of grateful recognition of his services occurred in 1827 during Charles’s naval mission to South America. This acknowledgement took the form of a beautifully decorated ceremonial “spadroon.”[3].

Fig. 1: Portrait of Charles Austen and his Sword

“[Charles’s] spadroon is a ceremonial sword with a canon-shaped cross guard and eagle-headed pommel. The loop guard is in the form of a rope, which is held in the eagle’s mouth, and loops around the canon. The grip is made of carved ivory. The steel blade has been etched with decorative patterns, with gilded decoration. The scabbard [or sheath for holding the sword] has been decorated with eagle and sun motifs on one side, and on the other side is inscribed the dedication to Charles Austen from General Simon Bolivar.”[4]

This wonderful artefact connects to a period in 1827, when, as captain of the frigate HMS Aurora (38 guns), Charles was one of the Royal Navy captains stationed in the West Indies. Part of this squadron’s duties was to provide various services of support for General Simon Bolivar, liberator of Spain’s former colonies in South America.

This past summer in England, I tried to find out more about the circumstances surrounding Charles’s receipt of his spadroon. It made sense to follow the clue which the historic inscription on the scabbard of the sword provides. That text reads: “Presented to Charles John Austen, R.N. commanding HMS Aurora at the City of Caracas, 1st March 1827 by Simon Bolivar the liberator of his country as a mark of his esteem.”

I knew that Charles kept a private journal during his years as Captain of HMS Aurora (1826-28). His writings are contained in nine notebooks in the collection of the Caird Library, which is part of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Once at the Caird Library, I expected to discover Charles’s entry for 1 March 1827 would provide a description of the sword’s presentation at a Venezuelan location, probably accompanied by Charles’s impressions of Bolivar. This was not the case. As Charles’s journal entry for that date reveals, he spent time at a Dockyard (most likely in Antigua) during the day.[5] That evening he entertained guests for dinner, the party concluding with “cards and liquors in the after cabin [of the Aurora].”[6] As further research revealed, Charles did not meet Bolivar until 20 April 1827, 50 days later.

So here was a mystery. Where and when did Bolivar present the sword and for what reasons did he select Charles for this honour? Answering this question will provide a glimpse of how Charles undertook various assignments, and activities which would not ordinarily occupy a naval captain on a station.

In a later post, I plan to place Charles’s receipt of the sword in the context of his career, exploring how, for a short period, Charles played a small part in British international diplomacy in South America. That narrative will also introduce several interesting individuals with whom Charles interacted: the artistic and ambitious British Consul in Caracas, Venezuela, Sir Robert Ker Porter, the Honorable Alexander Cockburn, His Majesty’s Envoy Extraordinary to the Columbian States, and the flamboyant and dynamic General Simon Bolivar, the illustrious military and political leader, who was known to his people as the Liberator and hero of the South American revolution. During his time in Caracas, Charles was welcomed by these men into the social and diplomatic life of the city.

[1] Owned by Austen descendent David Willan.

[2] See my blog for 26 May 2023, “Honouring Jane Austen’s Naval Brother Charles: The Story of his General Service Medal.” I have been recently told that Charles’s medal is very rare because of the two clasps. I thank Nick Ball of the Chatham Historic Dockyard for explaining to me that only four “Unicorn” claps were awarded, so the combination of one with the more common “Syria,” is almost certainly unique.

[3] A spadroon was lighter than a broad sword, because it was designed to both cut and thrust.[3] Earlier this year, Charles’s sword became part of the exhibit “Command of the Ocean,” at the Historic Dockyard, Chatham, Kent, England.

[4] Many thanks to the sword’s owner, David Willan for the fine detailed description of its appearance.

[5]Antigua is the most likely location as Charles’s guests included Captain and Mrs Wilson of the 93rd, a Regiment, which was stationed there.

[6] Charles Austen, Private Journal, 1 March 1827, AUS/121.

Honouring Jane Austen’s Naval Brother Charles: The Story of His Naval General Service Medal

Fig.1: Charles Austen’s Naval General Service Medal[1]

In 1849 Charles Austen received a distinguished award, the Naval General Service Medal. It was created by Queen Victoria in recognition of participation in significant naval actions between 1793 and 1840, such as an important single-ship capture of an enemy vessel, a larger naval engagement, like the Battle of St Domingo (1806), or a major fleet action, such as the defeat of the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar (1805).[2] The medal shows a left facing effigy of the Queen on one side and the figure of Britannia on the other. It hangs by a white ribbon edged with dark blue. Clasps, each designating the action for which the participant is honoured, are affixed to the ribbon.

Charles’s ribbon carries two clasps: “Unicorn 8 June 1796,” a reference to a single ship action by the 38 gun frigate, HMS Unicorn,[3] and “Syria” which refers to an extensive campaign in Syria in 1840.[4] These actions are like bookends to a 42 year period during Charles Austen’s long naval career. He was a 16 year old midshipman when the Unicorn triumphed over the much larger French frigate, La Tribune (44 guns). By 1839, during the action in Syria, he was the 60-year-old captain of HMS Bellerophon (80 guns). In this blog, I will explore the two naval actions which Charles’s medal recognizes and consider the significance of this award for Charles.

HMS Unicorn vs La Tribune: A dramatic chase and capture

Those aboard HMS Unicorn on 8 June 1796 would long remember that day. As dawn broke, the Unicorn, while cruising west of the Scilly Islands, sighted and gave chase to an enemy frigate, La Tribune.[5] During the day, the French ship ran before the wind, and although the Unicorn gained on her target, she was also subjected to well directed fire, resulting in damage to her mast and rigging. Undeterred, the Unicorn kept up the chase and a running fight for 10 hours. According to her captain, Thomas Williams, “at half past ten at night, having [run 210] miles, we [came] up alongside our antagonist and gave him [broad] sides for 35 minutes.”

As the smoke cleared, the Unicorn realized that she was still in considerable danger. La Tribune was, in Williams's words, “attempting by a master manoeuvre to cross our stern and gain the wind.”[6] Williams and his men responded by “instantly throwing Unicorn’s sails aback, by which means the ship gathered stern way, passed the enemy’s bow, regained her former position”[7] and renewed the attack. The triumphant Williams continued: “the effect of our fire soon put an end to all manoeuvre for the enemy’s ship was completely dismantled,[8] her fire ceased, and all further resistance appearing ineffectual, they called out they had surrendered.”[9] It was a spectacular triumph of seamanship and bombardment for all those aboard the Unicorn.

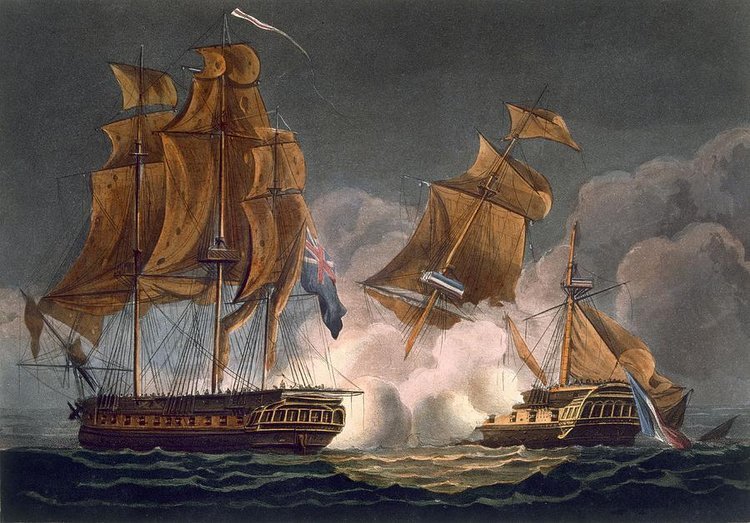

Fig. 2: Capture of La Tribune by HMS Unicorn on June 8th 1796.[10]

Only similarly significant single ship actions during the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802) were deemed worthy of the Naval General Service Medal.[11] The Admiralty recommended only those actions which counted as exceptional accomplishments in which the captain and the men had displayed marked courage and excellent seamanship, and the action was completed with as little loss of British lives as possible. The capture was also deemed praiseworthy if the enemy vessel, although damaged, could readily be repaired and refitted. In such instances, the ship could be recommissioned into the British Navy, thereby adding to the British fighting forces while at the same time reducing the enemy’s fleet.

Evidently, the taking of La Tribune by the Unicorn satisfied these expectations. With a crew of 251 compared to the enemy’s 337, Williams and his men undertook a daring and challenging action, which required bravery, stamina and perseverance. They managed to sustain a running fire for 10 hours over a distance of 210 miles. Moreover, Captain Williams’s leadership was exemplary. Throughout the action he displayed “judicious and seamanlike conduct.”[12] The enemy’s final desperate strategy to cross the Unicorn’s stern and gain the wind was “skillfully defeated”[13] by Williams’s quick thinking and his men’s rapid response. An extraordinary feature of the action was that La Tribune failed to inflict any casualties aboard the Unicorn, whereas 37 men on the Tribune were killed, and 15 were wounded, including her captain, Commodore Moulson. In addition, La Tribune was a valuable prize - only three years old, well built and well designed. She was repaired and commissioned into the British navy as HMS Tribune.[14]

To be a participant in an action of this importance surely thrilled the young Charles Austen. It was his first experience of a long and complex pursuit and capture. We don’t know what specific part he played. As a senior midshipman, he might have been involved in commanding a group of guns in action during the prolonged chase. Charles must have felt some reflected glory, given the public praise for the Unicorn’s remarkable feat. Certainly, the Austen family rejoiced when, soon after the Unicorn’s return to port, King George III knighted Captain Thomas Williams as a reward for his gallant bravery. The Austens had a personal reason for being delighted since Captain Williams had married Mrs Austen’s niece, Jane Cooper, two years earlier. For Charles, the Unicorn action demonstrated what fame and fortune a naval career might bring. If he developed expert naval skills and was lucky enough to have auspicious future commissions and assignments, he too might enjoy a life of adventure, honour and riches. That Charles did come by adventure and honour, at last, is signalled by his award of the second clasp designated “Syria.”

HMS Bellerophon (80) and the Syrian campaign 1840

“Syria” refers to the capture of the Egyptian held fort, St Jean d’Acre, on 4 November 1840 by Austrian, British and Turkish forces and the operations connected with it along the coast of Syria. What was Charles’s involvement in this offensive?

In April 1838, Charles was commissioned as captain of HMS Bellerophon, an impressive ship of the line with a crew of 650, and mounting on her lower, upper and quarter decks seventy-two 32 pounder guns and six 68 pounder guns. Among her crew were Charles’s only sons, nineteen-year-old Charles John, as master’s mate, and fourteen-year-old Henry. When the Admiralty dispatched reinforcements to the western Mediterranean that year, the Bellerophon was among the ships deployed on this mission.[15]

The political mood in the western Mediterranean at that time was tense as Mehemet Ali, the Viceroy of Egypt, had forcibly expanded his control into Syria. Britain and other allied powers demanded he withdraw. Hostilities began when the combined fleets of Britain, Austria and Turkey assembled close to Beruit in August 1840. The Bellerophon, together with HMS Hastings (74 guns) and HMS Edinburgh (74 guns) bombarded the town, which surrendered on 3 October. Tripoli was evacuated by October 22nd, leaving Ali with one last stronghold, the reputedly impregnable fortress of St Jean d’Acre with its surrounding town.[16]

Fig. 3: Bombardment of St Jean d’Acre, 3 November 1840[17]

At 2:00 pm on 3 November, the British and her allies mounted an intensive attack on the town of St Jean d’Acre,[18] its citadel and adjacent fortifications. The first division of British ships, initially led in by HMS Powerful and followed in order by the Princess, Charlotte, Thunderer, Bellerophon, and Revenge, was supported by a second division led by the Turkish admiral[19] with seven additional British warships, three Austrian and two Turkish vessels. The firing, once begun, “waxed furious.” The smoke obscured visibility even before the ships anchored. “The defenders, … [who] wrongly supposed the enemy would not venture close to the fortifications, were deceived as to the exact stations of the [attacking] ships, and thereby gave their guns too great an elevation.”[20] As Clive Caplin has described the scene, “the roar of the cannon was tremendous and incessant. A hail of enemy missiles whistled in all directions over the fleet, while a tempest of shot and shell poured down on the batteries and citadel of the town.”[21]

At 4:30 pm, the defenders suffered a catastrophe. A large powder magazine in the town blew up with a frightful explosion causing dense clouds of smoke. Upwards of 1200 people were killed. Quantities of debris fell on the Bellerophon, which continued to fire at any indications of resistance. During three and a half hours of constant action under Charles’s effective leadership, the Bellerophon expended 160 barrels of gunpowder and 28 tons of cannonballs.

Fig. 4: HMS Bellerophon leading the bombardment of the Syrian fortress at Acre[22]

By 6:00 pm all firing ceased. In addition to the devastation of property and lives caused by the explosion in the town, 300 were killed in the batteries and almost all the guns at the sea face were disabled. The Austrian Archduke Friedrich, who commanded the troops, led a landing party of allied soldiers to capture the citadel. This force, united with 5000 men who arrived from Beruit, took possession of the town of St Jean d’Acre. The combined navies’ action in this last Allied victory in the Egyptian-Ottoman war was complete. The only task left was the transfer of 2000 prisoners to Beruit, a task which Charles Austen shared with three other vessels.

What might this campaign have meant to Charles? Personally, he had the satisfaction of being part of a combined international force which successfully completed a large and significant naval action. He could be proud of his men who had deployed Bellerophon’s gun power with steady and effective industry. To his great relief, Charles's two sons survived unscathed, in fact he lost no men in the intense bombardment.

Subsequently, in addition to being awarded the “Syria” clasp for his participation in the campaign, Charles was picked out for further honour for his particular performance in the action. On 18 December 1840 he was one among only thirteen British captains and one Lieutenant who were made Companions of the Order of the Bath (Military Division), a prestigious British order of Chivalry founded by King George 1 in 1725. Moreover, the Syrian action, which illustrated his competence in battle, enhanced Charles’s naval record and likely contributed to his selection for what would be his last commission, his appointment in1851 as Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies and China Station.

Fig.5: Badge of the Companion of the Military Division of the Order of the Bath

[1] Owned by Charles’s direct descendent David Willan, the medal in currently on display at the Historic Dockyard, Chatham in the exhibit, “Command of the Oceans.”

[2] Other fleet actions include: Camperdown (1797), the Nile (1798), Copenhagen (1801), Abukir (1801).

[3] Only four individuals from the Unicorn action were still alive at the time this clasp was awarded.

[4] 6,978 individuals received this clasp.

[5] Unicorn’s action began as a pursuit, in company with HMS Santa Margaritta, of two French frigates the Tribune, and the Tamise. The Santa Margaritta quickly took the Tamise. The Unicorn continued to chase the Tribune.

[6] Thomas Williams to Admiral Kingsmill, 8 June 1796. The text of Williams’s letter is from a cutting of a newspaper report affixed to the back of a print, titled “The capture of La Tribune by HMS Unicorn …,” after Francis Chesham, in the possession of the National Trust, Gunby Estate, Lincolnshire.

[7] See “Sir Thomas Williams, Royal Naval Biography, ed. John Marshall, 1827.

[8] Only her mizen mast was left standing

[9] Thomas Williams to Admiral Kingsmill, 8 June 1796.

[10] After a painting by Thomas Whitcombe, published in The Naval Achievements of Great Britain from the year 1793 to 1817, London, 1817.

[11] Only 32 single ship actions were recognized.

[12] “Sir Thomas Williams, Royal Naval Biography, ed. John Marshall, 1827.

[13]“ Sir Thomas Williams,” J.K Laughton, revised Andrew Lambert, Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

[14] La Tribune was originally the French frigate, Galathee, launched in 1793. As HMS Tribune, her career in the British navy was short lived. See my blog “Jane Austen’s Naval Brother, Charles, and La Tribune: Milestones in a Naval Career, 1 August 2022.

[15] My account draws on Clive Caplan’s article, “The Ships of Charles Austen,” JAS Report for 2009, 154-5.

[16] See W.L Clowes on the 1840 Syrian campaign, paragraph 17, URL https://pdavis.nl/Syria.htm. The fort had been considerably strengthened since its occupation by the Egyptians in 1837. The defences were very strong towards the sea, where the works mounted 130 guns and about 30 mortars.

[17] By Lt Col William Freke Williams, published in England’s Battles by Sea and Land, 1857.

[18] According to Clowes, “the town was low standing on an angle presenting two faces to the sea, both walled and covered with cannon - in one place a double tier.” See paragraph18.

[19] He was Captain Baldwin Wake Walker RN.

[20] See Clowes, paragraph 11.

[21] See Caplan, 155.

[22] Signed and dated by John T. Baines, Dec. 19, 1840.

Jane Austen and The Festive Season at Chawton Cottage

I like to imagine how the Christmas season was celebrated at Chawton cottage in December 1809, the year which found Jane, Cassandra, their mother and their friend Martha Lloyd settled in their new Hampshire home. Jane’s letters give no hint of the scope of festivities.[1] However, we can be confident that certain activities were enjoyed and perhaps new forms of conviviality adopted.

Fig.1: Chawton Cottage[2]

The women had moved to Chawton during July, and although the timing was not ideal for planting and harvesting the range of fruits and vegetables they would cultivate in future years, they surely took the prospect of festive eating seriously and made sure to acquire the materials they needed. Consulting Julienne Gehrer’s books about Regency meals and their preparation reveals a range of tempting recipes. Their first festive season in Chawton may have included feasting on roast turkey,[3] and delicacies such as ragout of veal, fricassee of turnips, white soup and orange flavoured sponge cake.[4]

Fig. 2: Dining with Jane Austen by Julienne Gehrer

This was also the season for special hymns and carol singing. Jane, Cassandra and Martha had grown up as a rector’s daughters and Mrs Austen had supportively participated in her late husband’s parishes of Steventon and Deane. Now resident in Chawton all four women would have worshiped at the nearby church of St Nicholas. It is likely that traditional hymns, such as “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night,” “Joy to the World,” and “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” were incorporated into Advent and Christmas services and were well known to the Austens and Martha Lloyd.

Fig.3: Martha Lloyd’s Household Book, introduction by Julienne Gehrer

Continuing the singing of favourite hymns at home was another pleasure of the season. Jane was an accomplished pianist and a willing accompanist. Moreover, she had access to a variety of musical material. Her sister-in-law, Elizabeth, wife of her brother, Edward, had transcribed the music for “Adeste Fideles,” also including verses in the original Latin.[5] Such manuscripts were regularly shared amongst the family, so Jane may have had her own copy of Elizabeth’s work. Jane developed a large repertoire of piano pieces making it likely that she could play a variety of religious Christmas and Advent music. Presumably those in the Cottage also appreciated a spirited tune such as the one in Jane Austen’s music albums[6] titled “Nos Galan,” which is Welsh for New Year’s Eve.

In the years following 1809 other family members gathered at Chawton Cottage during the twelve days of Christmas. In a letter written 3 November 1813, Jane reports that they are “likely to have a peep of Charles and Fanny at Christmas.” This could mean even more voices united in song!

May your holiday be a musical one, if that is your wish. In 2022, as in many Decembers past, my family has joined neighbours and friends to sing carols together in the chill Nova Scotian air while gathered round an illuminated fir tree under the tower of our small village church. It is magical!

Fig.4: The Scene of Carol Singing

Season’s Greetings,

Sheila

[1] There is a gap in her correspondence extending from 26 July 1809 until 18 April 1811.

[2] In a letter from 29 November 1812, Jane refers to “eating Turkies” as a “very pleasant [Christmas Duty].”

[3] These foods are mentioned in either Martha Lloyd’s Household Book or the Knight Family Cookbook.

[4] “Adeste Fideles” translates into English as “ O Come All Ye Faithful.” See “Austen’s Festive Music” in Jane Austen’s Regency World, Nov/Dec 2019, Issue 102, 50.

[5] The Austen Family Music Books, including Jane’s seventeen music albums have been digitalized by the University of Southampton. The tune of Nos Galan is now used for the carol “Deck the Halls with Boughs of Holly.”

New Details about Jane Austen’s Naval Brother Francis on the North American Station 1845-48

In my blog post for November 2020, I wrote about Jane Austen’s naval brother, Francis, as Admiral in command of the North American and West Indies Station from 1845 to 1848.[1] His was a peacetime commission. While on the northern end of the Station, his duties were to ensure the protection of the fisheries against the Americans, to make coastal surveys and to maintain a British presence in the colonial possessions of the area. His flagship, HMS Vindictive (50 guns), was known as a “family ship” for he had on board two sons, George (the chaplain) and Herbert (an officer) along with his nephew, Lt Charles John Austen II. He also brought along two daughters, Cassy and Frances, as his designated social hostesses. What follows are some brief glimpses of Sir Francis at work and at leisure on the Station. They are suggestive of his personality and some priorities at this stage in his life and career.

Quebec City, September 1846

Fig. 1: Admiral Sir Francis Austen

Admiral Sir Francis Austen was keen to explore the extent of his Station and he was diligent in doing so. It entailed travelling northwest from Halifax, Nova Scotia, his northern base, to reconnoitre the St Lawrence River as far as Quebec City. While there, Sir Francis Austen also led at least one excursion on land. According to the Quebec Gazette, he and his family “returned yesterday from a visit to the upper part of the province.” Meanwhile, the same issue reports a tragedy that occurred aboard the Vindictive. On the night of 24 September 1846, “a midshipman from the Vindictive fell overboard and drowned while the ship was at anchor in the harbour…. A lifeboy was thrown over immediately and every effort made to save him, but the body never rose again. It was eventually recovered.”[2] The young man was eighteen-year-old John E. Haig.

The loss of a crew member, especially of one so young, was a matter of great regret. Moreover, young Haig’s family was presumably known personally to Francis Austen for it was the captain’s prerogative to select the young men who would be training as midshipmen under his command. Given Haig’s age, it is likely he had been aboard since the Vindictive left England and was probably studying for his lieutenant’s exam. It was Austen’s unhappy task to inform Haig’s widowed mother of the tragedy. She subsequently arranged for a memorial plaque to be placed on the wall above the left balcony in the Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral in Quebec City and for a tombstone in the St Matthew’s church cemetery on Rue Saint-Jean. John Haig’s untimely death added a sobering touch to what must have been a fascinating trip for Sir Francis and his retinue into a French-speaking community in North America.[3]

Visiting Prince Edward Island: October 1847

The following year Sir Francis made a trip to the colony of Prince Edward Island in the Gulf of St Lawrence. This voyage was another opportunity for familiarizing himself with the scope of his command. It was also a chance to inspect a new navigational aid, the recently completed Point Prim Lighthouse. The light was situated on a point of land extending into the Northumberland Strait and marking the entrance to Hillsborough Bay and the colony’s principal port of Charlottetown. Prior to the choice of this site, the colony’s Lt Governor had consulted with Royal Navy captains about the most eligible location for the light, and he had concurred with their judgement.

The completed lighthouse was impressive. Its construction featured a “tapered, cylindrical brick structure covered in wood shingles and it measured 18.3 metres from base to vane.” The tower possessed a prominent but elegant taper and a projected lantern platform supported by brackets which was topped by a multisided cast iron lantern.[4] Those on board the Vindictive could appreciate why the Point Prim Light was already an excellent resource for navigators in the region.

Fig. 2: Point Prim Light, Prince Edward Island

Sir Francis’s voyage took him from the Point Prim Lighthouse and into Charlottetown harbour, where local colonial officials were apparently expecting to welcome him and his party onshore. Such would be the normal courtesy when the Commander-in-Chief of the Station had dropped anchor in the harbour for three days. However, they were disappointed, as revealed by a headline in The Examiner, a local newspaper. It read “Admiral Failed to Disembark.” In self-justification, Sir Francis wrote to the paper:

That we did not land was entirely owing to the heavy rain, which did not cease for many minutes together from the Saturday evening till 12 o’clock on Tuesday when I left Port. I beg further to add that it never was my intention to devote more than three days to visit; that it had nothing whatever to do with Politics; being solely for the gratification of personal curiosity, combined with a desire of becoming acquainted with every part of my extensive command.”[5]

Note the detailed, crisp, dismissive tone of the letter. Sir Francis precisely describes the quantity of rain which made a shore visit ill-advised. He assures the readers he did not intend to stay longer. He does not want his decision to be interpreted as a political affront. He stresses he was in the area out of personal curiosity.

The wording of this letter invites comment. Sir Francis’s reference to heavy rain seems a poor excuse: had he and his party gone ashore, they could have expected to be entertained indoors. Additionally, Sir Francis’s “desire to become acquainted with every part of my extensive command” is inconsistent with his behaviour. He had been happy to take his family party on shore at Quebec, why would he not explore Prince Edward Island on arrival, even if it meant waiting for better weather?[6]

Sir Francis’s letter leaves the impression of one who is unhappy to have his actions criticized. There is a note of authority which is void of real regret or apology. He chose the public forum of a newspaper to explain his failure to visit ashore. This may not have been the wisest choice as the formal and impersonal tone of his letter could have failed to placate the disappointed local officials and population. Maybe the decision to stay on board the Vindictive can be explained by reasons Sir Francis did not choose to reveal. His daughter, Cassy, was a dominant force in her father’s social and official planning. Perhaps she decided that her father and his retinue must avoid the inconvenience of getting wet, and her opinion held sway.[7] I have yet to discover whether Sir Francis ever became acquainted with Prince Edward Island.

Summers in Halifax, Nova Scotia: 1845-47

Sir Francis and his retinue ordinarily occupied summer headquarters in Halifax, living in the spacious and elegant Admiralty House, completed in 1819. He attended to his official duties and did what was expected of him socially but he preferred the company of his immediate family. He was an attentive father and particularly concerned that his daughters enjoy themselves, which meant they needed some means of circulating in public. Francis had grown up in a family that was devoted to gardening, so he was most likely appreciative of exotic plantings and varieties of trees and shrubs. Given these interests, the five-and-a-half-acre Horticultural Society Garden, the forerunner of what became Halifax’s Public Gardens, would be an attractive place to take his daughters.[8] It was comprised of handsome flower beds, winding paths, specimen trees, a pool and a stream along with a meeting place known as Horticultural Hall. The Garden was private: it was only open to subscribing members drawn from the wealthy, professional and administrative classes. However, someone of Sir Francis’s rank and position, as well as his accompanying family, would undoubtedly be welcome as guests. Strolling about in the Garden would let Sir Francis mix with the upper classes among the Halifax citizenry, which, from his point of view, also counted as good public relations.

Fig. 3: Mature elm trees dating to the 1840s with the Horticultural Hall in the background

One of the Vindictive’s officers, Jane Austen’s nephew, Charles John Austen II, may have favoured the Garden for his own purposes. While on shore in Halifax, he had met and fallen in love with Sophia Deblois, the daughter of a wealthy local merchant. The Garden was an ideal place for a courting couple to promenade, to enjoy conversations a deux as well as summertime band concerts. Perhaps Charles was able to escort his Sophia to the Garden’s annual fund-raising bazaar where “the music afforded by 2 Highland pipers and 3 military bands, also ministered to the enjoyment of the company, the wares for sale executed with the usual taste of the ladies.” [9] [10]

Fig. 4: Halifax Public Gardens in September. The Bandstand was built in 1887

Three colonial centres: Quebec City, Prince Edward Island and Halifax- these are places where one can catch a fleeting glimpse of Admiral Sir Francis Austen during his naval career from 1845-48. He can be found in both his professional and personal capacities displaying diverse characteristics – now grieving over a drowned young trainee officer, then seeking to justify his arguably discourteous behaviour, yet on other occasions showing concern for his public relations and his daughters’ social needs. In 1848 at the termination of his commission as Commander-in-Chief of the North American Station, the Vindictive brought Francis home to England. Thus ended his last appointment in the active sea service at the age of 74.

[1] See blog post for November 2020.

[2] See Charles Andre Nadeau, “One of Jane Austen’s brothers was in Quebec City 175 years ago,” Quebec City newspaper, the Chronicle-Telegraph, September 22, 2021.

[3] Charles Austen’s letters reveal that he had occasion to mourn the loss of two midshipmen, part of a prize crew that failed to bring a captured merchantman into Bermuda in November 1808. Charles wrote to Cassandra on 25 December 1808: “I have lost her [the prize] and what is a real misfortune the lives if twelve of my people, two of them mids.” See Sheila Johnson Kindred, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister, 216.

[4] Point Prim Lighthouse: https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_hi_eng.aspx?id=14835.The lighthouse maintains the same appearance today.

[5] Quoted in The Guardian (Prince Edward Island newspaper), 12 October 2013. I am grateful to Penelope Player of Charlottetown who alerted me to this reference.

[6]In terms of the current political mood on the Island, a local newspaper The Examiner provides a clue. The paper quotes an editorial from another current newspaper, the Islander “on the subject of a Petition which a little knot of Charlottetown shop-keepers have got up praying His Majesty not to continue (Governor) Sir H.V. Huntley in the Government of the Colony longer than the allotted timelife (presumably the paper meant “lifetime”).[6] Yet, it would not be the mandate of a visiting naval Commander-in-Chief to address a petition circulated by a ‘little knot” of local shopkeepers. So there does seem to be a pressing political issue to be specifically associated with Sir Francis decision to stay on board. He did not need to mention politics in his letter to the editor of the Examiner.

[7] See other references to Cassy’s domineering views in my blog about Sir Francis, November 2020.

[8] It was comprised the southern half of the current Halifax Public Gardens, fronting on what is now Spring Garden Road

[9]Charles married Sophia in September 1848. Two other officers from the Vindictive married Halifax girls that year: W. D. Jeans, Sir Francis’s secretary, wed Bess Hartshorne; Officer William King-Hall married Louisa Foreman.

Notes about the Horticultural Society Garden are courtesy of Halifax Public Gardens guide, Susanne Wise.

Photo Credits:

Fig 1: Private collection

Fig 2: Lighthouse friends

Figs: 3, 4: Sheila Kindred